I was a guest speaker recently on a live webinar convened by Revolutionary United Front (RUF), “On the Need for Radical Activism at the Present Moment.” I was invited by RUF to speak about the new public statement I published in partnership with About Face: Veterans Against War on Medium in April, “The Militarization of US Government Response to COVID-19 and What We Can Do About It.”

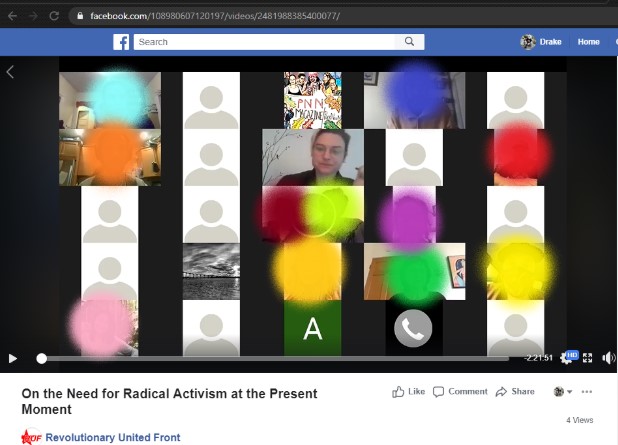

Just over an hour into the meeting, NeoNazis hacked my live presentation.

This is not new. NeoNazis have adapted their legacies of violence to the digital age. Their Zoombombing has become more prevalent in the COVID-19 pandemic, and includes digital attacks on synagogues, Black church gatherings, school classes, and social justice events.

With the new Black Lives Matter uprising, white supremacist violence has also escalated, both on the streets and digitally. Black folks now simultaneously face a much higher death rate from coronavirus, extreme police brutality and murder, unprecedented domestic police militarization, and the violent white supremacist forces which are generally protected by the police. The digital realm is one arena where anti-Black harassment, verbal violence and threats continue to increase.

As Zoombombing attacks continue to grow in frequency and viciousness, we need better preparation. Security measures like passwords, waiting rooms, disabling screen-sharing, and other best practices can deter some attacks. But some of these NeoNazi trolls are technologically sophisticated, though politically regressive. Here’s my story of fighting back live on Zoom, and some recommendations on what you can do if confronted with a similar situation.

Putting the Neo in Nazi: #Eugenics Zoombombing

The webinar’s panel of experts discussed a diversity of subjects that all related in some way to the impact of COVID 19–from viral epidemiology (with Dr. Michael VanElzakker of Harvard Medical School) to the poor people’s movement for homefulness (from POOR Magazine). I was the fifth presenter, and things were feeling heavy. So I began by inviting everyone to take a breath, and sharing a piece of art.

[I describe the art for folks on the phone] “If we get this right, we never have to go back to normal. How powerful is that? With this scale of pandemic, with this scale of death and crisis, we have an opportunity. And that’s what everybody’s talking about here. The Chinese word for ‘crisis’ is written using two characters that are combined to make a new meaning. The first character alone means ‘danger,’ and the second character alone means ‘opportunity.’”

I continue, “So we have an opportunity here to re-make our world: in the midst of this crisis, to reconnect with one another, re-build [hacker scribbles all over the art in yellow] together–Somebody’s drawing on the screen, that’s awesome.”

“I don’t know if you’re for or against this image. But welcome!” I laughed.

After attempting to diffuse the situation with humor, I continued with my presentation.

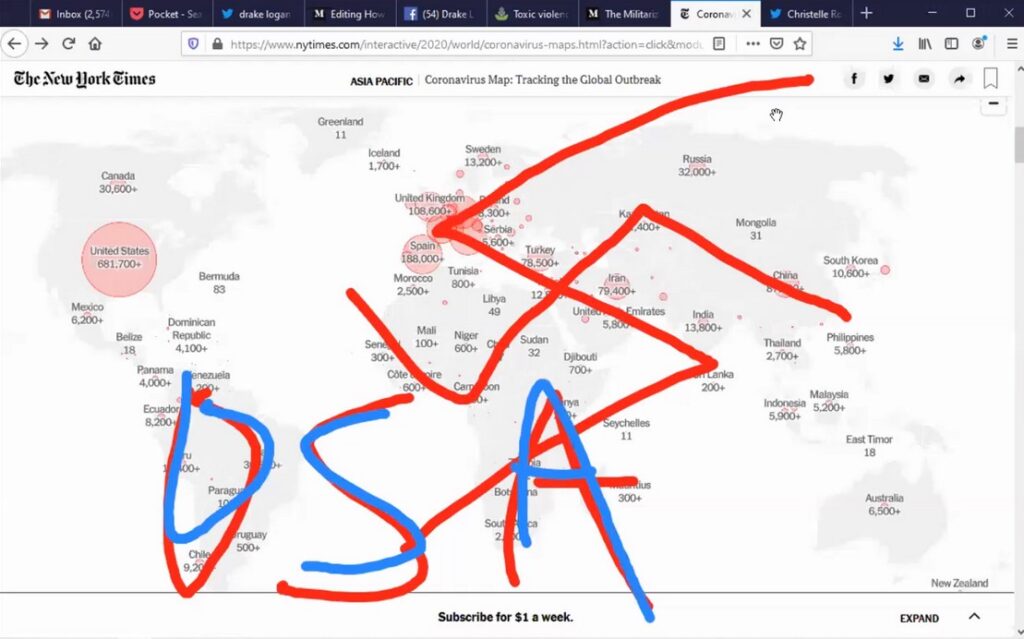

Immediately upon screensharing the New York Times data-visualized world map of confirmed COVID-19 cases, the hacker scribbled a swastika on the screen, covering the entirety of Africa, Europe, and Asia, along with the Middle East, and the letters “DSA” below.

Then the Zoom host paints it black, disabling screen-sharing to defuse the Zoombomb.

I continue into the black: “What I want to talk about is scale. Hopefully we can get the scribbling to go away, because I want to show this map. We have a hacker or something.”

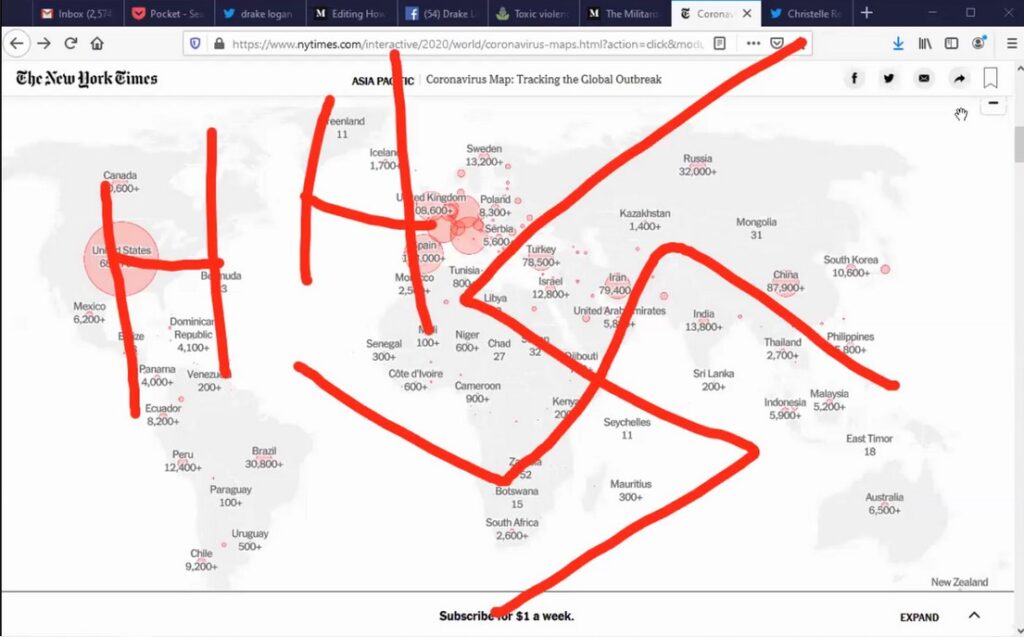

While the “DSA” could be a red-baiting reference to the left-wing socialist organization Democratic Socialists of America, a swastika over the world COVID-19 case map seems to argue for eugenics. I return to screen-sharing the COVID-19 map. Three seconds later the below Nazi hack appears. I set a firm boundary, because the repeat imagery is undeniably fascist.

“Okay, please stop, whoever’s doing that. That is violent to us all, and to me, myself.”

The host disabled screen-sharing once more. But I wanted the map on screen to help make my point, so I tried sharing my screen again, and again. Each time I attempted to continue with my presentation, the racist scribbling continued.

I needed to demonstrate through my words and actions that their attempts at disruption were ineffective. Their goal is to disrupt. Ours is to stay the course.

“So we are putting out key demands and analysis on a regular basis. And I’m going to try and share my screen again–because I’m brave like that and I don’t let them get me down.”

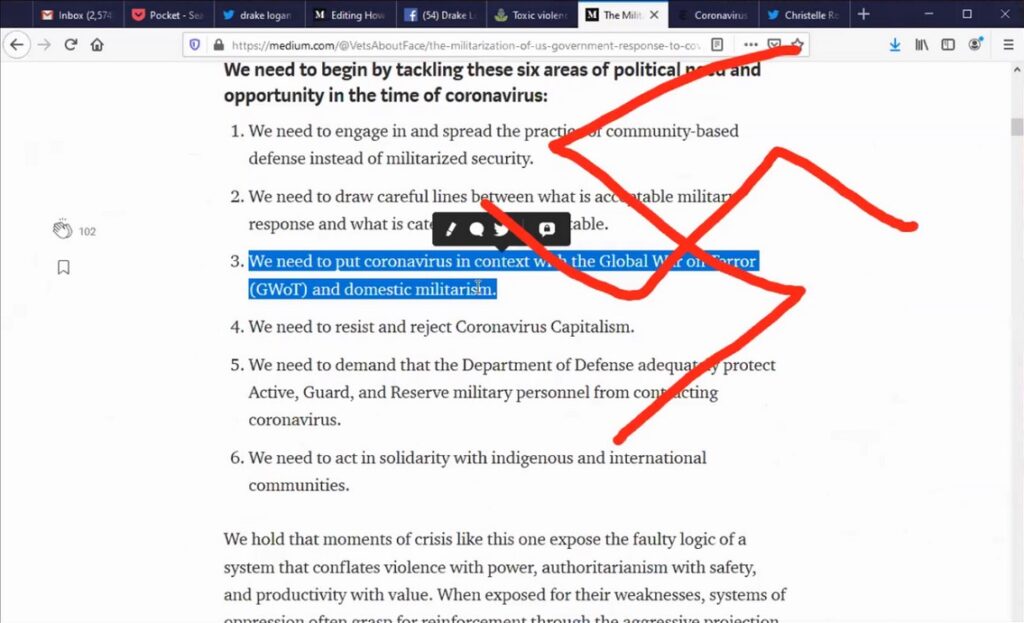

[I screen-share our first statement’s demands] “Here’s what we started to do–” [1.5 seconds after our text appears, a swastika is drawn across it] I’m reading the item highlighted in blue (below) in my summary of our key demands–when the swastika appears. Our demand says: (3) “We need to put coronavirus in context with the Global [so-called] War on Terror (GWoT) and domestic militarism.”

What better snapshot of where our country is at with militarism than a NeoNazi knee-jerking a swastika over that exact point? I keep going. I read aloud all of our demands–for example, limiting the government’s bending of its own rules on how the military cannot act domestically, and calling for community-based safety instead of militarized security for our towns.

I ignore the hackers, and close the presentation.

“I’ll stop there, and I look forward to your questions.”

Use your prior experiences and facilitation skills to your advantage

I taught US Government 101 during the Trump campaign, election, and the first year of his regime. Many of my students were immigrants of color, some wore hijab, some lacked documentation, and some were impacted by the Muslim Travel Ban and were unable to go home because they would not be let back in.

The morning after Election Day in 2016, we spent the whole class discussing our fears for what was coming–not only from Trump, but also from those he emboldens. It was both painful and healing, and it was the best class I’ve ever taught. Teaching US Government at CUNY for those three years meant being nimble and prepared to support my students in whatever fresh hell the Trump regime had just aimed at them–so I was prepared for just about anything shocking and awful that day on Zoom.

We all have examples in our own lives and experiences we can draw from to better deal with Zoombombing. For example, you may have:

- redirected a chaotic classroom;

- not let a counter-protest drown you out or bend your messaging too much into the fray;

- answered the question you wish the journalist had asked you instead of the one they actually did;

- asserted yourself with a family member who has challenged your life decisions.

When you are violently disrupted online, it is important to make your boundaries clear, while also demonstrating that you will continue your work and stay on track. Bring what you know from other contexts to bear. These interventions are examples:

- “If you keep doing x, I’m going to y.” (classroom redirection)

- Verbally challenge your opponent without going off message or giving them too much energy or attention (lesson from street protests)

- Even if a journalist asks you a problematic or loaded question, you redirect the discussion back to your talking points.

- Even if your family challenges the very core of your beliefs, values, or identity, you can continue to live in and cultivate your own dignity and respect for yourself and others. Re-center in why you do what you do, and the values that enliven you.

Years of experience practicing how to stay on point in these other contexts helped me deal with the NeoNazis as well as I did. You too can riposte them. As you enter the Zoom room, say to yourself: I know how to surmount obstacles laid in my path, I know how to stay on track. Repeat after me: I can best these NeoNazis.

Staying on course in your presentation is one of the most critical things you can do if Zoombombed. NeoNazi disrupters want to bend your agenda to their will and overtake your airtime. Don’t let them get either one. Name what is happening, then ignore them and move right along while the Zoom host kicks them out.

Debriefing about the hack may be useful, but it need not overtake your event. In fact, your debrief may be more effective after folks have had time to reflect on what happened.

Love,

P.S. Join us! You can follow About Face here and here, and you can follow me here.

Drake Logan is a researcher-activist on US-led global warfare in the post-2001 era. He specializes on military toxins. In 2018, he and other activists collected citizen-science data on depleted uranium (DU) during live bombing along the fence lines of Pōhakuloa Training Area on Hawai’i Island–where the Army confirmed it used DU. It has not been cleaned up. Logan is a PhD Candidate at the City University of New York, The Graduate Center, and will receive his PhD this summer. He also holds an Interdisciplinary Master’s from The New School for Social Research, specializing on international human rights, the international laws of war, and modern Middle East history and politics. He has engaged in activism against US-led warfare since he witnessed the events of September 11th, 2001, as a senior in high school.

Drake was just interviewed in-depth on ResearchPod. He has also been published in the academic journal Cultural Dynamics, on Medium, PublicsLab, Common Dreams, and by About Face: Veterans Against the War. He is currently finishing his first book, Searching for Pōhakuloa: A Citizen Scientist’s Journey in Aloha ‘Āina. He lives in Northern California. You can follow him on Twitter at @dr3keness, and find his work at www.drakelogan-edu.com.